ENVIRONMENTAL SLAVERY: AMERICA’S ORIGINAL SIN CONTINUED

Contributors: Sacoby Wilson, Sakereh Carter, and Aliyah Adegun

Have you ever considered where your trash goes? Who cultivated the vegetables that you eat everyday? Who made the table in your living room? The contaminants that people are exposed to, so that you could serve pork at the family dinner? The American lifestyle is inherently oppressive, the small luxuries that we take for granted come at the expense of others’ health and well-being.

In the United States low-wealth black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) are disproportionately impacted by a myriad of environmental and occupational hazards including landfills [1], incinerators [2], power plants [3], leaking underground storage tanks [4], traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) [5], occupational heat stress [6], pesticide exposure [7], lead poisoning [8], industrial animal operations [9] (See Figure 1), and much more. According to the National Black Environmental Justice Network (NBEJN), 68%, 39%, and 56% of Blacks, Latinx, and Whites live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant [10]. Twelve out of 378 coal-fired power plants that emit the most hazardous compounds including sulfur dioxide, nitric oxide, and particulate matter are located in low-income communities of color [11]. People of color are exposed to 38% more air pollution relative to Whites [12]. Latinx populations are exposed to 124% more traffic-related air pollution relative to Whites and 42% of Latinx live near Superfund sites [13]. The inequitable distribution of environmental hazards in low-wealth communities of color is linked to America’s continued subjugation, oppression, and exploitation of low-income and non-White communities.

America’s history of oppression and exploitation can be described as detestable. We colonized a nation inhabited by the rightful owners of this country and intentionally slaughtered 90% of Native Americans with blankets contaminated with smallpox [14]. We enslaved 10.5 million Africans and kept them in chains for almost three centuries [15](See Image 1).

The commodification of enslaved Africans allowed America to become the most powerful nation on the planet. Free labor afforded American companies the seed money necessary to accumulate billions of dollars and build multi-generational wealth [16]. Racism continues to protect the economic capital and status of Whites. In the 1850s, slave owners were compensated for slaves that died prematurely for their “financial losses” [17]. Today, racism denies African-Americans equal economic footing or reparations, even though the average wealth in Black households is $140,000 relative to $901,000 for White households in 2016 [18].

Historically, two major aspects of racism upheld the institution of slavery: (1) systemic racism and (2) White silence. Similar to the institution of slavery, racism justifies the poisoning of BIPOC, and America’s silence allows for the perpetuation of environmental injustice. Specifically, racist ideologies that engender the disparate concentration of environmental hazards in BIPOC, systemic racism in environmental planning and policies, and national inaction of governing bodies and citizens to rectify environmental injustice leads to environmental slavery. Environmental slavery is defined as the uneven distribution of polluting industries in low-income communities of color, race-based distribution of environmental benefits and burdens that regulate the accumulation of social and economic capital, and the devaluation of low-resource communities [19] (See Image 2).

The term environmental slavery is interchangeable with environmental racism and classism. Environmental classism describes the inequitable distribution of environmental hazards in low-wealth communities, specifically locally unwanted land uses (LULUs). Environmental classism encompasses social norms that devalue low-wealth communities, disregard for political autonomy in low-wealth areas, and economic forces that drive the siting of LULUs in low-wealth neighborhoods [19]. Conversely, environmental racism describes the unequal treatment of people of color with respect to environmental policy and enforcement, intentional siting of toxic facilities in communities of color, and the fortification of discriminatory practices with local, state, and federal law [19]. Environmental slavery impedes community prosperity by introducing noxious land uses that impact economic development, social opportunity, and community potential. For example, LULUs diminish property values and land desirability which prevents low-income people and people of color from selling their homes and depresses regional investment. A study conducted at Pennsylvania State University found properties located near high volume landfills (500 tons or more) exhibited a 12.9% decrease in property value which diminished with distance from the landfill [20]. Currie et al., 2015 performed an in-depth analysis of property values in Texas, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Florida located near 1,600 newly established power plant operations and revealed an 11% decrease in property value, an effect that decreased with distance [21].

During the Flint lead crisis, 6,000–12,000 residents were exposed to high concentrations of lead in their drinking water [22] (See Image 3). Years later when residents wanted to sell their homes they felt stuck, like they, “we’re never going to be able to move out of the city.” Lead is a neurological and reproductive toxicant that can impair the viability of offspring and contribute to infertility generations after initial exposure [23]. The deadly element stunts families’ growth, robbing them of the joy of children. In addition, it impairs one’s intellectual capabilities through lead induced IQ reduction, preventing those exposed from attaining education and economic capital that could advance one’s community [24].

WHO KNOWS HOW MANY BEAUTIFUL BLACK MINDS WE’VE LOST TO TOXIC LEAD? HOW CAN YOU SAY NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND IF WE ALLOW TOXINS TO DAMPEN THEIR POTENTIAL? HOW CAN WE TALK ABOUT PUTTING AMERICA FIRST, IF WE DO NOT PUT OUR KIDS FIRST?

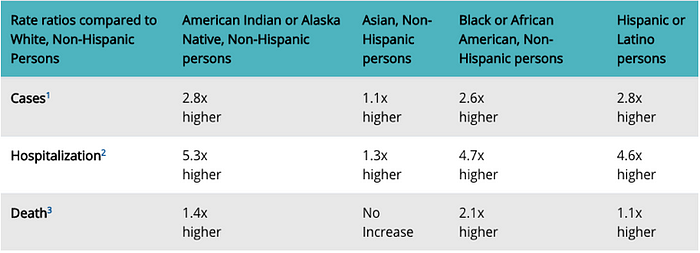

Moreover, low-wealth communities of color are barred from experiencing the ecological benefits of health-promoting infrastructure and grapple with a higher proportion of social and environmental factors that negatively impact health and impair quality of life [25]. This has been observed during the COVID-19 crisis which disproportionately affects low-income Latinx and African-American communities [26] (See Table 1). Black and Latinx individuals are three times more likely to contract COVID-19’and twice as likely to die from the virus [27]. Approximately, 6% of Whites succumb to the virus under 60 years old relative to >25% of Latinx individuals [27]. In Fairfax County, a particularly wealthy county in Washington D.C, the COVID-19 infection rate is four times greater in Latinx individuals relative to Whites [27]. A Latinx resident of Fairfax County is still recovering from COVID-19 but has to choose between their health and livelihood. “We have to go out to work,” she said. “We have to pay our rent. We have to pay our utilities. “We just have to keep working [27].”

“We have to go out to work,” she said. “We have to pay our rent. We have to pay our utilities. “We just have to keep working.

Differential COVID-19 outcomes can be attributed to pre-existing environmental hazards and social inequities that WERE NEVER ADDRESSED IN THIS COUNTRY. The amalgamation of environmental hazards that decrease property values, lack of health-promoting infrastructure, and toxic pollution creates an inescapable loop of poor educational opportunities, lack of desirable jobs, lower intellectual potential, and low wealth which exemplifies environmental slavery.

The second pillar of environmental slavery describes the inequitable cost-benefit relationship between White-affluent communities and low-income communities of color. Tessum et al., 2019 found that communities of color breathe an excess 56% of air pollution that’s driven by a high consumption of goods and services in White communities [28] (See Image 4). On average, wealthy American homes produce 25% more climate-altering pollutants that contribute to climate change than low-wealth homes [29]. The combination of White supremacy and privilege, economic and political power, and systemic racism safeguard White-affluent neighborhoods from undesirable land uses and exposure to toxic substances.

Conversely, low-income communities of color are disproportionately impacted by hazardous facilities and polluting entities that decrease economic capital and deteriorate health. For example, race is the single best predictor for determining the location of hazardous waste facilities [30].

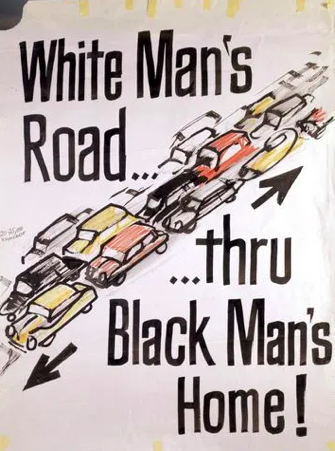

Moreover, highways are typically constructed in Black neighborhoods exposing residents to high concentrations of traffic-related pollution [31] (See Image 5). Traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) can decrease lung function by 20% and industrial facilities are 79% more likely to be located in African-American neighborhoods [32]. Particulate Matter (PM2.5, PM10), a toxic component of air pollution buries deep into the lungs and contributes to lung dysfunction, asthma, respiratory disorders, mental impairment, cardiovascular disease, premature mortality, birth defects, and cancer [33] (See Figure 2).

Aside from environmental hazards, occupational exploitation disenfranchises low-resource communities while private companies attain inconceivable economic wealth. In 2018, US prisoners across 17 states protested “modern-day slavery” conditions in prisons by participating in a 3-week hunger strike [34]. Prisoners provide cheap customer service and craft various household items that are sold to private companies at a cheaper rate than outsourced labor. To add fuel to the fire, Trump’s Make-in-America initiatives encourage exploitative practices by glorifying all American labor. In California, prisoners are paid $1 an hour to quell wildfires even though the average firefighter salary is $74,700 in the state [35] (See Image 6).

According to Colorado.gov, wildfire smoke is associated with throat irritation, difficulty breathing, lung dysfunction, enhanced asthma severity, and premature death [36]. Approximately, “40% of U.S. inmates suffer from a chronic medical condition” and 31% of inmates are more likely to have asthma relative to the general population [37]. The CDC recommends that individuals with chronic health conditions protect themselves from wildfire smoke [38]. Approximately, 17,000 prisoners are involved in the unjust nexus of carceral slavery, often making less than two dollars an hour [34].

Approximately, 17,000 prisoners are involved in the unjust nexus of carceral slavery, often making less than two dollars an hour (vox.com).

Occupational exploitation isn’t solely reserved to Whites, many people of color have exploited people in their own communities. As the US recycling industry boomed in the 1970s, recycling industries bribed local government officials which in turn welcomed the construction of recycling facilities. These recycling programs were touted as “occupational opportunities” for local communities, even though recycling exposed workers to “loud noise, jagged objects, chemical, and biohazards” [39] (See Image 7). Many people of color and first-generation immigrants took advantage of the entrepreneurial opportunities associated with recycling and established their own recycling programs.

The third pillar of oppression is individual bias and prejudice against low-income and people of color. The contempt for indigenous communities and communities of color is so deeply ingrained in our society that we use these individuals to soak up the most poisonous compounds on the planet. DEFORMITIES, LOW BIRTH WEIGHT, and INFERTILITY, we sterilize these communities and use their babies to soak up toxic compounds so that we can sustain our consumer habits and companies can satisfy their insatiable desire for money.

Profit motives and the disdain for low-resource communities leads to the dehumanization and devaluing of these populations that justifies the creation and maintenance of ‘sacrifice zones’.

In Uniontown, Alabama, a community with an average income of less than $12,000, residents are exposed to 4 million tons of coal ash and receive trash from 33 different states [40] (See Infographic 1). Coal ash contains toxic heavy metals including lead, mercury, and arsenic, and may contaminate the air and groundwater supply. Exposure to lead, arsenic, and mercury is linked to reproductive toxicity including infertility and miscarriage [41].

In Perry County, residential streets are bathed in coal ash and community members breathe in the waste material everyday. A resident from Perry County noticed that the coal ash stripped the paint off his car. “If that’s what it’s doing to my truck, imagine what it’s doing to me,” said Gibbs [40].

“If that’s what it’s doing to my truck, imagine what it’s doing to me”

Sacrifice zones are maintained by economic and political forces that often don’t align with the interests of low-income communities of color. In 2016, the Arrowhead Landfill filed a 30 million dollar lawsuit against Uniontown community-based organizations alleging that protestors engaged in character assassination, slander, and made false claims about the facility [42] (See Image 8).

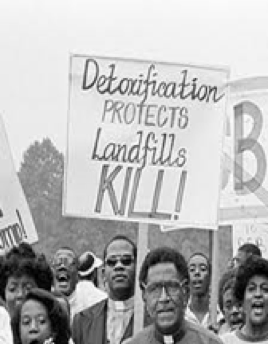

Economic and political forces are reinforced by regional law enforcement and unchecked global militarization. In 1983, residents of Warren County, NC protested the siting of a polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) landfill in their community. PCB exposure is linked to reproductive dysfunction, immunosuppression, neurological effects, impaired development, and cancer [43]. Over 500 protestors were arrested in Warren County and 60,000 tons of PCB-laced soil was dumped into an ill-constructed landfill [44]. A former Warren County civil rights activist commented on the Warren County, NC case in 1994. “They use Black people as guinea pigs. Anytime there is something that is going to kill, we’ll put it in the Black area to find out if it kills and how many. They don’t care. They don’t value a Black person’s life [45] (See Image 9, 10).”

“They use Black people as guinea pigs. Anytime there is something that is going to kill, we’ll put it in the Black area to find out if it kills and how many. They don’t care. They don’t value a Black person’s life.”

The policing of Black and Brown bodies across the world perpetuates the oppression of low-resource communities by restricting individual agency, pacifying resistance, placing constraints on community autonomy, and protecting the interests of White and wealthy companies.

In order to address the deeply ingrained culture of exploitation and oppression in low-income communities of color, BIPOC researchers must use environmental slavery as a framework to tackle EJ issues. Abolishing centuries-old practices of environmental slavery requires community engagement, access to health-promoting infrastructure, and reduction of environmental inequity. From a policy standpoint, a just system will consider the health impacts of all proposed environmental practices and implement ‘green zoning’ that will revitalize overburdened communities that have been denied environmental reparations and justice for centuries.

CEEJH provides a set of recommendations to legislators, research scientists, and other stakeholders [46]:

- Incorporate detailed environmental justice clauses into local, state, and nationwide policies. Integrating EJ into legislative proposals will normalize EJ consideration and prioritize EJ action at all levels of governance.

- Engage with designated environmental justice communities. Community outreach builds trust and gives a voice to communities that are often neglected in the policymaking process. Communities ARE the experts in their environments and lack of thoughtfulness can lead to toxic frustration. Instead, communities should feel validated and any of their concerns should be addressed with evidence-based research conducted by partnering research institutions. Community-informed policies, plans, and directives reflect the needs of the community and increase a sense of value which is critical to dismantling environmental slavery. Community outreach also enhances transparency, as health impact assessments can be shared with community members to enrich environmental health education.

- Conduct cross-disciplinary analyses to address environmental justice issues. Environmental justice is inherently cross-disciplinary requiring the expertise from policymakers, researchers, community members, community-based organizations, city planners, and more. Lack of cross-disciplinary communication hinders project cohesion, a deep understanding of environmental issues, comprehension of discipline-based limitations, and overall practicality.

- Local, state, and national governments should conduct health impact assessments (HIA) for all permit applicants to assess the health impacts associated with proposed operations. Environmental injustice harms the health of low-income communities of color, a health-modulating factor that’s completely outside of their control; thus, it’s our responsibility to protect the health of populations exposed to toxic substances.

- Policymakers should be knowledgeable about environmental justice issues. Policymakers must forge relationships with community members in order to protect their health and understand the intersection between all social and environmental pathogens. Specifically, governmental entities should establish a community advisory board composed of local community members that advise local politicians and policymakers on EJ issues.

- Politicians and polluting entities must be held accountable for their actions. Policymakers must be monitored at all steps of the policymaking process including policy development, implementation, and efficacy of enforcement. Polluting entities must be held accountable for lack of mandated environmental remediation or discriminatory zoning practices.

- ULTIMATELY, all public health officials should seek to reduce exposure to environmental hazards in conjunction with constructing just, equitable, and health-promoting infrastructure in low-income communities of color.

REFERENCES

- Campbell, R., Caldwell, D., Hopkins, B., Heaney, C., Wing, S., Wilson, S., . . . Yeatts, K. (2013). GUEST COMMENTARY: Integrating Research and Community Organizing to Address Water and Sanitation Concerns in a Community Bordering a Landfill. Journal of Environmental Health, 75(10), 48–51. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26329647

- Wilson, S., Aber, A. Ravichandran, V. Wright, L., Muhammad, Omar (2017). Soil Contamination in Urban Communities Impacted by Industrial Pollution and Goods Movement Activities. Environmental Justice, 16–22. Retrieved September 1, 2020 from https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2016.0040

- https://www.thesentinel.com/communities/prince_george/news/local/dr-sacoby-wilson-presents-report-detailing-environmental-injustice-in-county/article_10dbf8b3-9a35-5e5f-9d55-22c0046b8810.html

- Wilson, S., Zhang, H., Burwell, K., Samantapudi, A., Dalemarre, L., Jiang, C., Rice, L., Williams, E., & Naney, C. (2013). Leaking Underground Storage Tanks and Environmental Injustice: Is There a Hidden and Unequal Threat to Public Health in South Carolina?. Environmental justice (Print), 6(5), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2013.0019

- Commodore, A., Wilson, S., Muhammad, O. et al. Community-based participatory research for the study of air pollution: a review of motivations, approaches, and outcomes. Environ Monit Assess 189, 378 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-017-6063-7

- Moda, H. M., Filho, W. L., & Minhas, A. (2019). Impacts of Climate Change on Outdoor Workers and their Safety: Some Research Priorities. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(18), 3458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183458

- Arcury, T. A., & Quandt, S. A. (1998). Chronic Agricultural Chemical Exposure Among Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers. Society & natural resources, 11(8), 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941929809381121

- https://www.dw.com/en/lead-poisoning-reveals-environmental-racism-in-the-us/a-53335395#:~:text=A%20recent%20study%20shows%20that,environmental%20injustice%2C%20the%20authors%20say.

- Wilson, S.M., Serre, M.L., 2007. Examination of atmospheric ammonia levels near hogCAFOs, homes, and schools in Eastern North Carolina. Atmos. Environ. 41,4977–4987.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.12.055; https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF18/20191120/110247/HHRG-116-IF18-Wstate-HerringE-20191120.pdf

- https://www.scribd.com/document/33842120/Air-of-Injustice-African-Americans-and-Power-Plant-Pollution

- https://www.naacp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CoalBlooded.pdf

- https://thinkprogress.org/why-air-pollution-is-a-racial-issue-745d90a8c8f9/

- https://rhg.com/research/a-just-green-recovery/

- https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/american-history-myths-debunked-the-indians-weren-t-defeated-by-white-settlers-app4gGHFX0G0L7tx--7wAA

- Micheletti, S., Bryc, K., Esselmann, S., Freyman, W., Moreno M., Poznik G., Shastri, A. Genetic Consequences of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the Americas (2020). The American Journal of Human Genetics, Vol. 107(2): 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.06.012; https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2019/11-12/slave-ship-clotilda-wreckage-africatown/

- https://atlantablackstar.com/2013/08/26/17-major-companies-never-knew-benefited-slavery/8/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/23/business/economy/reparations-slavery.html

- https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/2019-economic-commentaries/ec-201903-what-is-behind-the-persistence-of-the-racial-wealth-gap.aspx

- Wilson, Sacoby. “Environmental Justice Movement: A Review of History, Research, and Public Health Issues.” Journal of Public Management & Social Policy vol. 16, I (2010): 19–50.; https://rhapsodyinbooks.wordpress.com/2009/02/12/february-12-1968-black-sanitation-workers-strike-in-memphis/

- Ready R (2010) Do landfills always depress nearby property values? Journal of Real Estate Research 32: 321–339.

- http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/rwalker/research/TRI_CurrieDavisGreenstoneWalker.pdf

- Ladapo et al. “Lead Pollution in Flint, Michigan, U.S.A. and Other Cities.” International Journal of Environmental & Science Education vol. 11, 5 (2017): 1341–1351; http://www.tox-expert.com/2017/07/03/update-flint-michigan-drinking-water-crisis/

- Vigeh, Mohsen et al. “How does lead induce male infertility?.” Iranian journal of reproductive medicine vol. 9,1 (2011): 1–8.

- Reuben, Aaron et al. “Association of Childhood Blood Lead Levels With Cognitive Function and Socioeconomic Status at Age 38 Years and With IQ Change and Socioeconomic Mobility Between Childhood and Adulthood.” JAMA vol. 317,12 (2017): 1244–1251. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.1712

- Wilson, Sacoby. “An Ecologic Framework to Study and Address Environmental Justice and Community Health Issues.” Environmental Justice vol.2, 1 (2009): 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2008.0515

- https://youtu.be/_TnW8xlJ0No; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

- https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/ct-nw-nyt-coronavirus-racial-disparity-20200706-ltntynugwjheplqe5swxsvizfe-story.html

- Tessum, Christopher W et al. “Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial-ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 116,13 (2019): 6001–6006. doi:10.1073/pnas.1818859116; https://sites.temple.edu/historynews/2016/02/29/cartoonist-samuel-r-joyner/

- Goldstein, B., Gounaridis D. and Newell, P. The carbon footprint of household energy use in the United States (2020). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117(32): 19122–1913010.1073/pnas.1922205117

- https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/toxic-wastes-and-race-at-twenty-1987-2007.pdf

- https://e360.yale.edu/features/connecting-the-dots-between-environmental-injustice-and-the-coronavirus; https://energyhistory.yale.edu/library-item/white-mans-roadthru-black-mans-home

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents/ochp_2015_near_road_pollution_booklet_v16_508.pdf; Apelberg, B. J., Buckley, T. J., & White, R. H. (2005). Socioeconomic and racial disparities in cancer risk from air toxics in Maryland. Environmental health perspectives, 113(6), 693–699. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7609; Wilson, S., Zhang, H., Burwell, K., Samantapudi, A., Dalemarre, L., Jiang, C., … Naney, C. (2013). Leaking Underground Storage Tanks and Environmental Injustice: Is There a ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE PLAN 2025 Page 75 Hidden and Unequal Threat to Public Health in South Carolina? Environmental Justice, 6(5), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2013.0019

- Manisalidis, I., Stavropoulou, E., Stavropoulos, A., & Bezirtzoglou, E. (2020). Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review. Frontiers in public health, 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00014; Dockery D. W. (2009). Health effects of particulate air pollution. Annals of epidemiology, 19(4), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.018; Lee, B. J., Kim, B., & Lee, K. (2014). Air pollution exposure and cardiovascular disease. Toxicological research, 30(2), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.5487/TR.2014.30.2.071; https://www.ecowatch.com/u-s-epa-sued-for-failure-to-issue-air-pollution-standards-1881589230.html

- https://www.vox.com/2018/8/17/17664048/national-prison-strike-2018

- https://www.careerexplorer.com/careers/firefighter/salary/california/; https://www.cnbc.com/2018/08/14/california-is-paying-inmates-1-an-hour-to-fight-wildfires.html

- https://www.colorado.gov/airquality/wildfire.aspx

- https://gejp.es.ucsb.edu/sites/secure.lsit.ucsb.edu.envs.d7_gejp-2/files/sitefiles/publication/PEJP%20Annual%20Report%202018.pdf; https://www.wbur.org/commonhealth/2009/01/16/prisoners-dont-receive-adequate-care-by-steffie-woolhandler-md

- https://www.cdc.gov/air/wildfire-smoke/chronic-conditions.htm

- https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/garbage-wars; https://www.npr.org/2019/08/20/750864036/u-s-recycling-industry-is-struggling-to-figure-out-a-future-without-chinabelt

- https://earthjustice.org/features/campaigns/photos-a-toxic-inheritance; https://www.revealnews.org/episodes/scuttling-science-rebroadcast/; https://www.ceejhlab.org/infographics

- Kumar S. (2018). Occupational and Environmental Exposure to Lead and Reproductive Health Impairment: An Overview. Indian journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 22(3), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_126_18; Kim, Y. J., & Kim, J. M. (2015). Arsenic Toxicity in Male Reproduction and Development. Development & reproduction, 19(4), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.12717/DR.2015.19.4.167; Henriques MC, Loureiro S, Fardilha M, Herdeiro MT. Exposure to mercury and human reproductive health: A systematic review. Reproductive Toxicology. 2019 Apr;85:93–103

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jun/02/uniontown-alabama-landfill-defamation-suit-green-group

- Faroon, O., & Ruiz, P. (2016). Polychlorinated biphenyls: New evidence from the last decade. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 32(11), 1825–1847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748233715587849

- McGurty, E. M. (2000). Warren County, NC, and the emergence of the environmental justice movement: Unlikely coalitions and shared meanings in local collective action. Society & Natural Resources, 13(4), 373–387. doi:10.1080/089419200279027; https://semspub.epa.gov/work/HQ/174868.pdf

- Harris,M. G. 1994. Interview by author. Tape recording. Red Hill, NC, 2 September.; http://www.opalpdx.org/movement-history/; https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/645961.Dumping_in_Dixie

- https://www.princegeorgescountymd.gov/DocumentCenter/View/27132/Environmental-Justice-Commission-Report-Final-PDF; http://www.btbcoalition.org/index%20page%20images/ENVIRONMENTAL%20JUSTICE%20PLAN%202025_PrinceGeorges.pdf